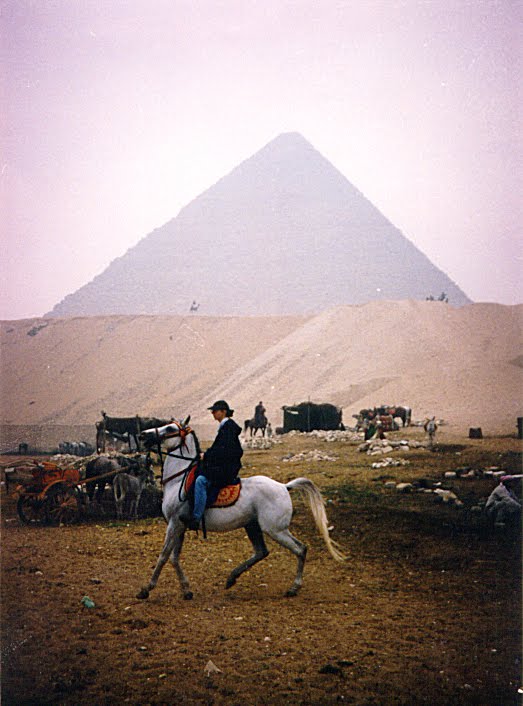

Midan at-Tahrir, downtown Cairo

I found this article this morning and it carried me right back to my year in Cairo.

I, too, found that the greatest struggle in Cairo (besides keeping weight on) was finding any Arab willing to talk to you in Arabic instead of English. Taxi drivers, in the beginning, were my only subjects to practice on, and I am convinced they were all natural born linguists. I took hundreds of taxi rides in my year there and I only remember ONE DRIVER who admitted he knew only Arabic. I should have hired him for the rest of the year!

As the fellow in the article states, you soon find yourself pretending not to be an English-speaker so they'll be forced to speak Arabic with you. I don't know what the writer looks like, but I'm blonde with blue eyes, so my first try was telling the driver I was German and spoke no English.

I should not have been shocked when he answered me back in fluent German, at which point I had to confess that, though I am 50% German, I only know 5% of the German language.

Eventually I had better luck telling them I was Norwegian. If I was too tired to argue, I just got used to speaking Arabic to Arabs who always spoke English to me. I mean, after all, we were both just trying to learn a new language.

The only surefire way to be immersed completely in the local language was to get out of town. I was extremely fortunate to get invited to a four-day wedding in a remote village north of Cairo in February of 1994. Four days of being grilled non-stop in the Egyptian dialect by numerous generations of very curious villagers did more to advance my fluency than the entire year of colloquial classes at The American University of Cairo.

Struggling to practice Arabic in Egypt

By PETER PRENGAMAN, Associated Press Writer Peter Prengaman, Associated Press Writer – Mon Mar 16, 1:36 pm ET

CAIRO, Egypt – It was a simple question that I know I posed correctly in Arabic.

"What time does the movie 'Stolen Kisses' begin?" I asked the guy at the ticket booth in my best Egyptian dialect.

"At 7 o'clock," he responded in heavily accented and barely understandable English, as if I hadn't just spoken to him in Arabic.

"How much are the tickets?" I said in dialect, refusing to speak to him in English.

"Twenty Egyptian pounds," he answered, again in English.

I had come to Cairo for a month to do an intensive Arabic course after studying the language three years at UCLA, and had become accustomed to such linguistic battles. With a small group of men hovering to watch this ridiculous conversation unfold, it was time to employ a surprise maneuver that would be my best chance for linguistic triumph.

I shook my head in disbelief, and then, switching to Modern Standard Arabic, and speaking louder, asked the man in a sarcastic tone: "Do you even speak Arabic?"

The question produced laughter from him and the audience, but it had the desired effect: By asking in the written and more formal Arabic that only educated Arabs are truly versed in, I had changed the equation. Instead of trying to show me he spoke English, he was now on the hook to show me he had a good level in standard Arabic — in essence, that he had a certain level of education.

"Yes, of course," he said in Arabic, the standard variety, no less. "You are funny."

I told him that since we were in Egypt I figured we might as well speak Arabic. We both had a laugh, and after a few more exchanges we shook hands. I told him I would come back later to see the movie.

When it comes to culture, history and even Arabic, Egypt is arguably the center of the Arab world. Egypt strikes a middle ground, both philosophical and geographical, between the more liberal Arabic-speaking countries like Morocco to the west and conservative Gulf nations like Saudi Arabia to the east. And as Egyptians will proudly tell you, their dialect is the most widely understood worldwide thanks to Egyptian movies and music that for decades have been beamed into Arab households across the Middle East.

Despite all that, trying to learn Arabic in an Arabic-speaking country can be difficult. For one thing, Egyptians jump on any chance they get to practice English, even if they only know a few words. And spoken Arabic dialects are hard to master no matter which country you try to learn them in, because they're often so wildly different from standard Arabic that they seem like a different language.

Most universities in the United States and other English-speaking countries only teach standard Arabic, and not the dialects of particular countries. Standard Arabic is the written language of schools, diplomacy, banking and news. It's not, however, a language that anyone outside of those circles speaks on a daily basis.

So does it make sense to learn it? Wouldn't it just be better to study a dialect? These are questions that perplex every student of Arabic. My short answer is that if you just learn a dialect (likely on your own, because few places teach them), you may be limited to that one country. Also, dialects are not widely written. You might be able to read a street sign, but not a newspaper or magazine if you don't know formal Arabic.

The reality is that the Arab world has a standard written language and then several spoken dialects (so as not to offend Arabic purists, I should also mention Classical Arabic, the language of the Quran and Arabic's highest written form).

When I arrived in Cairo and got in a taxi, I thought I was in the wrong country. Because I had had very little training in Egyptian dialect before arrival, I spoke to the driver in standard Arabic. He understood me — most Egyptians comprehend it but can't converse in it — but I had no clue what he said in reply.

Eleven terms of high-level Arabic at UCLA, including advanced courses with poetry, Quranic verses and full compositions, and I couldn't even shoot the breeze with this guy!

Within a few weeks, I was more comfortable with the dialect, in large part thanks to an intensive course at the International Language Institute that focused on helping advanced students morph their standard Arabic into something they can use on the street.

One of my coolest experiences in Cairo happened at a kiosk. Buying a newspaper in Arabic, I struck up a conversation with the guy working at the kiosk, Ahmed. An avid reader, Ahmed had a very good level of standard Arabic and was proud to use it. A few minutes later, his friend Mohammed arrived.

Mohammed saw my newspaper and told me he couldn't read or write since he had never gone to school. Curious about the United States, as many Egyptians are, Mohammed had question after question. But I struggled to understand a lot of what he said because he of course spoke in dialect.

So Ahmed jumped in, translating for me Mohammed's questions into standard Arabic. I would then respond in standard Arabic, and if Mohammed didn't understand, Ahmed would then translate what I said back to dialect. The fascinating 45-minute conversation hit home for me just how complex Arabic can be, even for native speakers.

The second challenge in Egypt is communicating in English. As in many foreign countries, there are a handful in Egypt who speak it amazingly well, while the vast majority have a level somewhere between zilch to intermediate.

The difference is that so many Egyptians seem to believe they need to use what they know with foreigners. Of course, so few foreigners speak Arabic that Egyptians assume it's better to use English — and getting them to change that assumption can be tough.

"Speak to me in English," the guy at the train station in Alexandria told me when I asked for a ticket in Arabic.

I did just that, responding in unfiltered and normal-speed English just to test this guy's chops (after all, he had questioned my manhood, in linguistic terms).

The result? He stared at me blankly, and we were reduced to gestures and grunts.

This passion for English may have several roots. Egypt is a former British colony. English-language movies, TV and culture are ubiquitous. Plus, English is the worldwide language of business, and Egyptians are some of the toughest negotiators you'll ever meet.

On the street, it comes down to this: An Egyptian man who knows 10 words of English will often, literally, use them over and over in conversation, even if you both are speaking in Arabic and it's clear you understand. For example, while speaking Arabic, when he comes to a place where the word "good" could be used, and he knows that word in English, he'll insert it.

That can be disorienting. When you don't understand something, it's hard to know if he used a few words in English that you didn't recognize because of poor pronunciation, or if you simply just didn't understand the Arabic.

Attempting to avoid English, by week two I was telling taxi drivers and others I came across that I was Spanish or French, and that I didn't speak English. That neutralized English somewhat, but pretending that I didn't understand my native language felt strange.

Of course, studying Arabic in Egypt will help students develop a much better grasp of the language than anything they could do in the United States.

Egyptians may be enamored of English and have a hard-to-master dialect, but Arabic is the national language and it's alive and well. Add to that fun and very social people — not long after meeting someone, you often find yourself at a cafe sipping tea and smoking flavored tobacco out of a hookah pipe — and you've got a formula for what any stint abroad should be: an adventure.

Friday, March 20, 2009

Struggling to practice Arabic in Egypt

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment