Image courtesy Greg Mortenson, Central Asia Institute

I have been anxious to post my review of Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin's Three Cups of Tea. Unfortunately, no sooner had I finished it than I was compelled to start re-reading it. I cannot shake the feeling that this is the most important book I have read in years.

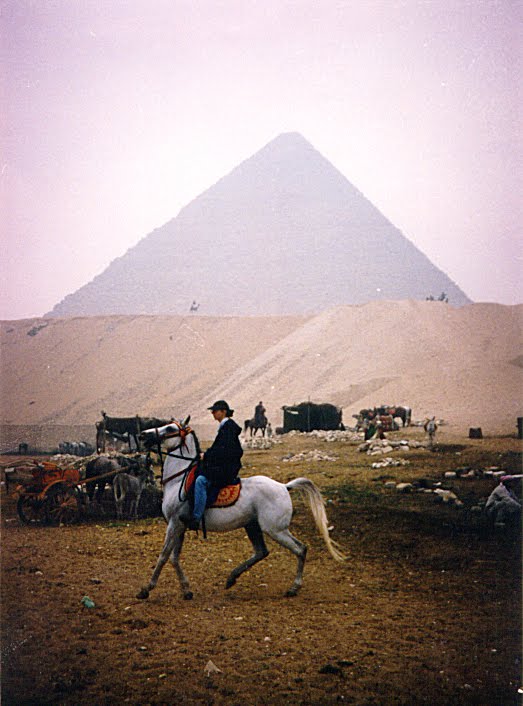

It is no secret to those who know me that the year I spent in Cairo (1993-1994) was a life-altering experience for me. (And frankly, I think they're a little sick of hearing about it.) Life in America is blinding with all its taken-for-granted comforts and readily-available basic needs. I remember being "poor" as a child in Kentucky, only eating Thanksgiving dinner one year thanks to a few bags of groceries (and the toughest chicken I have EVER attempted to chew) delivered unexpectedly by a local church group. I recall passing beggars on the streets of Madison, Wisconsin during my high school and early college years, and sympathizing with the plight of the homeless. But I knew nothing of poverty.

Images haunt me still from the streets of Cairo. There was the boy of eight or nine, dirty and completely naked, darting terrified through an extremely busy intersection one morning as I made my way to the university. His body carriage suggested he was severely handicapped. Traffic moved haltingly around him but never stopped. A traffic cop shot him glances as he ran past, but had to remain focused on preventing pile-ups, as traffic lights that were installed in the 1980's work perfectly but are still ignored completely by drivers. From my low perch in my black and white taxi, I soon lost sight of the boy.

Photo courtesy of Pexi from Helsinski Rock City

Photo courtesy of Pexi from Helsinski Rock City

It is no secret to those who know me that the year I spent in Cairo (1993-1994) was a life-altering experience for me. (And frankly, I think they're a little sick of hearing about it.) Life in America is blinding with all its taken-for-granted comforts and readily-available basic needs. I remember being "poor" as a child in Kentucky, only eating Thanksgiving dinner one year thanks to a few bags of groceries (and the toughest chicken I have EVER attempted to chew) delivered unexpectedly by a local church group. I recall passing beggars on the streets of Madison, Wisconsin during my high school and early college years, and sympathizing with the plight of the homeless. But I knew nothing of poverty.

Images haunt me still from the streets of Cairo. There was the boy of eight or nine, dirty and completely naked, darting terrified through an extremely busy intersection one morning as I made my way to the university. His body carriage suggested he was severely handicapped. Traffic moved haltingly around him but never stopped. A traffic cop shot him glances as he ran past, but had to remain focused on preventing pile-ups, as traffic lights that were installed in the 1980's work perfectly but are still ignored completely by drivers. From my low perch in my black and white taxi, I soon lost sight of the boy.

Photo courtesy of Pexi from Helsinski Rock City

Photo courtesy of Pexi from Helsinski Rock City There was another boy, this one perhaps going on twelve, standing inside Midan at-Tahrir (Cairo's central square and most congested area of the city) beating a horse who quite clearly had suffered a broken leg. An ill-fitting harness suggested a cart nearby, though I could not spot it. The underweight chestnut, one of his front ankles dangling uselessly, could not walk, and his eyes rolled back frequently in pain. The boy's face showed only fear as he repeatedly lashed the horse with a loose rein, trying in vain to move the beast out of traffic and towards home--where he would have to tell his family that the cornerstone of their family's income had been destroyed on his watch.

I also remember that I watched this scene unfold as I sat with my American roommate waiting to catch a minibus to the Pyramids. No doubt we were going riding. We both grew ill witnessing the pain of the horse, the fear of the boy, and anticipating the heartbreak of an already impoverished family--but I don't remember our jumping off the concrete traffic barrier we sat upon to offer our help.

Really, though--what could we have done? This was before cell phones and I'm quite certain calling 911 would have gotten us nowhere. We could lead a horse with a broken leg no better than the boy--and we certainly could not cure him. There was no point in trying to explain to the boy in our broken Arabic that his horse was fatally injured and needed to be put down. He knew that well enough. His instincts just could not allow him to abandon that horse--the single most valuable asset his family owned--to die alone in multiple lanes of high speed traffic.

Something inside us--inside me, anyway--told me not to interfere. It told me I could not change the course of events, nor could I fix them--all I could do was bear witness. And maybe there is some truth to that, but not enough. I am tired of being nothing more than a witness. I am sick from inaction--sick in mind, and sick in body.

Greg Mortenson, co-author of Three Cups of Tea and Director of the Central Asia Institute, witnessed similar levels of poverty as he wandered down from K2 in the Karakoram mountain range of northwest Pakistan--roughly the same time I was learning about poverty in Egypt. Greg was lost and broken by his failed attempt at the summit, which he had intended to dedicate to his younger sister, Christa, who had passed away the year before. Disoriented and exhausted, he stumbled into the small mountain village of Korphe and, in the course of the next few weeks, transformed from witness to agent of change. His tale is of an amazing man, but not a superhero. Greg Mortenson is a man, and that, I believe, is the underlying message that should be taken from his book.

We are raised believing that only superheroes can change the world--not simple men. And this becomes the perfect excuse to not even try. Thankfully, Greg was never taught this disabling message. Raised to believe that he could achieve anything, he did something--something extraordinary.

I don't believe that I can "do anything," and I'm not convinced that I ever did. Even after getting my Masters degree in Arabic in 1995, I failed to land a position with UNESCO and was too intimidated to even try the UN. My forays into the business world of Arabic-to-English transtaion never transpired to much of anything, and eventually petered out until I was left working in a profession whose only connection to Arabic was Arabian horses. And finally, despite the stated demand for Arabic speakers, I could not get a job with the FBI or State Department following 9/11. Even those of us (you might know us as bleeding heart Liberals) who stood firmly against our narrow-minded and war-hungry administration and sneered at government positions all through graduate school came to feel a strong obligation to provide voices of moderation on Capitol Hill and in US embassies around the world. I'll never forget summoning the courage to follow-up with the main office of the FBI after receiving my rejection letter to ask why, despite my education credentials, I would not be considered for an interview. They told me my application lacked self-confidence, and they needed people who believed they could do anything.

I may not be that person, but maybe I can learn to be more like her. I have sat and watched as 41 years of my life has passed--much of which I dedicated to helping people who didn't ask for it, didn't want it, all the while turning my back on the ones who did.

On April 5, 2008, Greg Mortenson will be speaking at a fundraiser for the Central Asia Institute in Downers Grove, IL. I don't know what's going to be on the menu, but it must be tasty at $100 a plate. Joking aside, that money will go far in the poorest, war-torn reaches of Afghanistan and Pakistan to educate children or provide their communities with basic services, such as safe water sources and basic medical care.

And maybe, just maybe, I can shake this man's hand, look into his eyes, and learn something that will make me believe that I can do anything.

Image courtesy Greg Mortenson, Central Asia Institute

Image courtesy Greg Mortenson, Central Asia Institute

1 comment:

You CAN do something. He is just a man. You R "just" a woman. All U have to do is believe in yourself and take the risks involved in trying to change at least a corner of the world.

Post a Comment